| CREATING A NEW STATE

Address by Dr. Martin Mansergh at the Seminar Dinner for the 4th Festival of History – 29th La Touche Legacy Weekend in association with Greystones Archaeological and Historical Society, Greystones Golf Club, Saturday, 30 September 2017, at 8 pm |

| I greatly regret that I was not able to attend the earlier part of the weekend to listen to a series of excellent lectures and discussions, but this morning I had to address a LAMA studies day on Brexit for councillors from around the country in Clonmel, and this afternoon I was attending the National Famine Commemoration in the Commons, Ballingarry, at the site of the 1848 rebellion. |

| A most distinguished and influential Huguenot family, the La Touches, and the branch based in Bellevue in Delgany that played a big part with others in the development of this town, is annually commemorated. The roads up to the Golf Club, Whitshed Road and Burnaby Road, remember other families involved. |

| The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 involved the tearing up of the promise of toleration made a century previously by King Henry IV of France, himself a Huguenot till he allowed himself to be persuaded that Paris was worth a mass. It was probably the worst political decision made by Louis XIV aggravated by the indefensible forcible conversion pursued by the dragonnades, one with long-lasting negative consequences, but that benefited the countries that took in Huguenot refugees. It boosted the rise of Prussia under the Great Elector, and would have been more of an asset to Ireland, if the Jacobite élite, the Wild Geese, had not been forced shortly after in the opposite direction. |

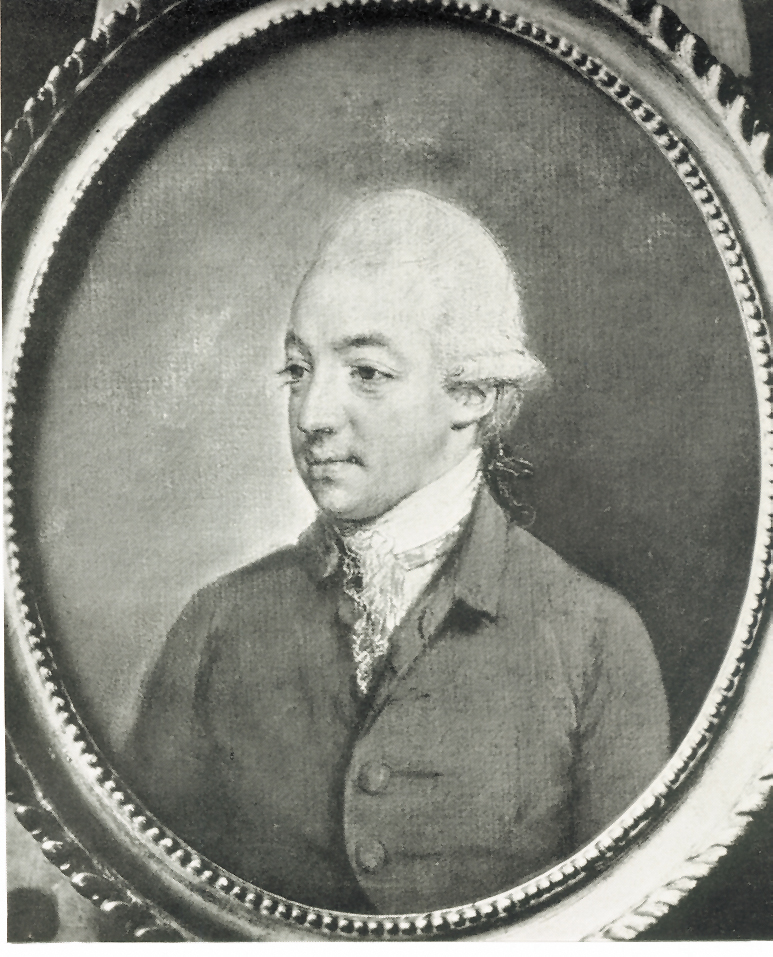

| I came across the Rt. Hon. David La Touche in many contexts; in the history of the Bank of Ireland founded in 1784, of which he was the first Governor; through several fine portraits of him and his family by Hugh Douglas-Hamilton, the exhibition of whose works I launched in the National Gallery in 2008; and because he was the principal resident of Rathfarnham in Marlay House, where he lived not far away from papermills along the Dodder, one of which owned by the Mansergh family made the paper on which Journals of the Irish House of Commons in the 1780s were printed. David La Touche was an MP in that body known as Grattan’s Parliament, and all the La Touches except for him voted against the Act of Union, which was injurious to the capital’s banking interest. Notwithstanding that, half a dozen family members served as MPs for all or part of the first 30 years of the Union Parliament. |

| Jacqueline O’ Brien, the wife of Vincent, in her magnificent book on the capital’s Georgian architecture co-authored with Desmond Guinness, Dublin: A Grand Tour, records a wonderful verse that served as a bank cheque drawn in favour of his wife by Richard Whaley, who was the then owner of 86, St. Stephen’s Green, now Newman House, once the headquarters of the Catholic University,the precursor of UCD. The versified cheque reads:

‘Mr La Touche, Open your pouch, And give unto my darling Five hundred pounds sterling: For which this will be your bailey, Signed, Richard Chapell Whaley’. |

| The most important connection that I had with the legacy of David La Touche is that as a public official I twice worked in his former town house, No. 52, St. Stephen’s Green, first of all on an upper floor when I was a First Secretary in the Economic/EEC Division of the Department of Foreign Affairs in the late 1970s, and then between 2008 and early 2011 as Minister of State with special responsibility for OPW. The ministerial office and outer office were in two of the fine high ceiling first floor reception rooms attributed to Angelika Kaufmann, a pioneering Swiss woman artist, who worked in Ireland in 1771, and a friend of David La Touche. He would have figured in the famous print of Grattan’s Parliament that the OPW art adviser Jacquie Moore recommended for my office walls, representing the beginnings of a constitutional nationalist tradition and honoured by ’82 men up to the time of Arthur Griffith. We also put up a picture from the 1830s of the Obelisk marking the Williamite victory at the battle of the Boyne, primarily because of my involvement in the project to restore and open the battlefield site, where then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern met twice with Dr. Ian Paisley, but it is also the case that the founder of the La Touche dynasty in Ireland, the Huguenot refugee, David Digues La Touche, fought at the Boyne. The largest painting in the room was one by Seán Keating, 1921. An IRA Column, probably based like Men of the South on a Cork flying column led by Seán Moylan. If only for geographical reasons, they were unlikely to have been the unit which blew up the Boyne Obelisk on the opposite wall. So there was something for every Northern visitor, regardless of tradition. |

| I came across an 1801 letter in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, today an enviably fine facility in Belfast’s Titanic Quarter, relating to the election of Robert La Touche as member for Kildare, from one Lewis Mansergh in Athy, which throws light on how electoral politics was conducted in other days. It is an apology for not being able to fulfil a voting pledge to Colonel John Wolfe, nephew of the Lord Chief Justice Lord Kilwarden, two years later hapless victim of the Emmet rebellion. Colonel Wolfe voted against the Union, and was dismissed from his offices. It was said he could not be purchased. The letter read as follows:

‘Dear Sir, Shortly after I had the pleasure of conversing with you at Athy, I wrote to the Duke of Leinster expressing my intention to support Lord Robert FitzGerald at the next Election for this County, and intimating a wish that I were left at liberty in respect of my second vote. The Duke informed me that a delicacy he had entertained prevented him from disclosing his sentiments at an earlier period, but that he now informed his friends that Mr. Robert Latouche had his sincere good wishes. The Duke did me the honour of calling on me, last Friday; and shortly after him came Mr. Latouche accompanied by Mr. Hamilton. I candidly told these gentlemen that Col. Wolfe was the gentleman of whom my judgment approved, and that if ever I had the opportunity of giving an uninfluenced vote that it would be given to him. Mr. Hamilton and the Duke of Leinster expected that his friends would support Mr. Latouche. I replied by saying that if I were to give my vote from you it would be contrary to my inclination as well as judgment. I must fear from the decided party which the Duke takes in support of Mr. Latouche, that I shall be prevented from serving you as I wish. ‘Tis true I am not dependent upon him for any part of my property, but I feel that if I were to oppose myself to his wishes, it would be doing an unbecoming, and perhaps, an ungrateful act. I shall now forebear to register the four freeholds I had intended. Excuse me for troubling you with this letter I felt it right to communicate its contents to you. I have the honour to be, Dear Sir, with great Respect & Truth your most humble servant. Athy, 16 November 2001, Lewis Mansergh’.

|

| The letter shows that even those who had the franchise, before the days of Catholic Emancipation and before the secret ballot, were not in practice always free in the exercise of it. It can only be speculated upon whether there were any financial reasons for the penurious Duke of Leinster, as he is described by Edith Johnston-Liik in her biographical dictionary The Irish Parliament 1692-1800, to back a La Touche, whose father had purchased the borough of Harristown in Co. Kildare off the duke in 1792 for £14,000, and who had succeeded to his father’s partnership in the La Touche Bank. The Hamilton referred to could have been the MP for Dublin County before and after the Union. Robert was the successor to his uncle Peter La Touche of Bellevue in ownership of 9, St. Stephen’s Green, subsequently the St. Stephen’s Green Club. The Rt. Hon David La Touche had been first Treasurer of the Kildare Street Club, when it was located in premises now the Royal College of Physicians. In a later generation, Percy La Touche was involved in the management of the Punchestown Race Course. His mother Maria was not in the vanguard of those pushing for what she called ‘Home Ruin’ or for democratic local government. Bellevue was demolished in the 1950s. Ainsi passe la gloire de ce monde. |

| It is appropriate that the sweeping democratic mandate for an independent Irish state secured in the December 1918 General Election coincided with the virtual introduction of a universal franchise, with women over 30 voting for the first time. The 1922 Irish Free State Constitution completed the process by lowering the voting age for women to 21, the same as for men. In that respect, the promise of the 1916 Proclamation was fulfilled, though further progress towards gender equality then stalled for half a century.

|

| It is appropriate that the sweeping democratic mandate for an independent Irish state secured in the December 1918 General Election coincided with the virtual introduction of a universal franchise, with women over 30 voting for the first time. The 1922 Irish Free State Constitution completed the process by lowering the voting age for women to 21, the same as for men. In that respect, the promise of the 1916 Proclamation was fulfilled, though further progress towards gender equality then stalled for half a century. |

| As I am sure has been said already, the political achievement of an independent Ireland over the past 100 years has been considerable. If one were to ask the question why has the Irish revolution, which inspired and encouraged many liberation movements round the British Empire beginning with the Indian National Congress, been more enduring than the internationally much more famous Russian one of October 1917, part of the answer has to be that Ireland forged a strong parliamentary tradition under the Union, albeit in opposition to it. Tsarist Russia left only a weak parliamentary tradition, and Lenin simply scrapped the Constituent Assembly, when the Bolsheviks won less than a quarter of the popular vote. |

| One of the fallacies of public discourse today is the notion that clientilism is rife in independent Ireland, because of our PR electoral system, which the people have no desire to change. Has no one heard of ‘pork-barrelling’ in the US Congress, a regular or rather irregular add-on to the legislative process? According to a book by James McConnel, Irish Parliamentary Party MPs in the early 20th century drove the Imperial Parliament to distraction by their habit of asking a multitude of questions about local issues, details of land purchase, the drainage of rivers in South Galway, and the provision of roads and piers. James O’ Mara MP for South Kilkenny even received a request forwarded by a local priest in 1906 to put down a parliamentary question on behalf of a woman who was complaining about a neighbour’s cow that was trespassing on her land. Putting down a question ‘could provide tangible evidence of an MP’s efforts on behalf of his constituents’, even though some MPs came back by boat and train nearly every weekend, a journey that took nine hours just to Dublin. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted in his famous book The Ancien Régime and the Revolution, there was a lot more continuity pre- and post-revolution in Ireland as well as in France. Irish politicians stay close to the people, perhaps one reason that extremism is kept in check. |

| The Union was initially promoted by the British as akin to a marriage, but as the perceptive writer and guardedly pro-Union Maria Edgeworth, who like Jane Austen avoided marriage, was aware, a married woman in 1800 had no rights, and if a union lacked passion or affection it could be disastrous. So it proved. Most British statesmen and commentators were scornful of the very idea of an Irish nation; it did not mean that they embraced the Irish as part of any British nation. While Napoleon successfully pulled out all the stops to prevent famine in France at the beginning of the 19th century, Britain in the 1840s was more concerned to put on the brakes, for fear of creating permanent dependency. National solidarity across the two islands was completely absent. The UK remains a very lopsided state in terms of English dominance. Isaac Butt, initially a unionist, later first leader of the Home Rule party, noted at the time: ‘When calamity falls upon us, we then recover our separate existence as a nation’. |

| The potentially historic compromise of Home Rule was given the run-around for half a century. The notion of a peaceful evolution of even 26-county Home Rule evolving into independence has no historical basis, or, as Garret FitzGerald once described it, it is ‘alternative history gone mad’. In a pro-Home Rule speech in Belfast in 1912, Churchill stated that ‘the separation of Ireland from Great Britain is quite impossible’. Prime Minister Lloyd George stated in 1917 in the House of Commons:

‘It is not a question whether it is to be in the form of a republic… The point is there is a demand for sovereign independence in Ireland … It is better that we should say that under no circumstances can this country possibly permit anything of the kind’. In 2014, there was no force involved, but politically the British Government did everything in their power to prevent the Scottish people voting for dominion independence as something quite distinct from devolution. |

| The foreseeable reshaping of Europe in line with the principle of national self-determination provided a unique moment of opportunity to achieve independence, at least for the greater part of Ireland. In a later interview in 1916 by a member of Cumann na mBan who was in the GPO, Moira Regan from Wexford, it was about having a national life of our own. In that regard, from the 1920s till today, that has been an emphatic success, provided it is not defined unrealistically as shutting out external influences, and even if the quality of national life can endlessly be argued about. |

| In the war of independence, the Irish people were on their own. Not a single foreign government, not the US, not France, not Germany, nor even the Soviet Union, could afford to alienate or offend the British Government, one of the key peace-making powers at Versailles. What support Ireland could garner was from public opinion, and, though victorious, Britain post-war faced a lot of problems, domestic industrial peace, colonial unrest, and above all heavy indebtedness towards America. In the last resort, with Northern Ireland secure, the rest of Ireland was expendable. |

| A lot of new countries experience civil war. Lee Kuan Yew, long-time Prime Minister of Singapore explained the phenomenon as the lack of long-standing legitimacy attached to a new form of government, which has to meet the challenge to its authority. There was a cost to independence, short- and long-term, the long-term one having been the propensity of self-perpetuating paramilitary groups to take the law into their own hands on the basis of a spuriously concocted legitimacy. One of the objects of the decade of centenaries, as defined by the Government-appointed Expert Advisory Group, chaired by Dr. Maurice Manning, is to hear the different narratives and to extend our sympathies, without having to abandon our loyalties. It is to the credit of the State and the Government that last year the centenary of the Rising was commemorated in a dignified, sympathetic and inclusive manner, and hopefully the sequel will be treated similarly. |

| The main achievement of the Irish Free State was to build solid civil institutions, to which nearly all political groupings came to adhere, and to retain public support for them. Extending independence and gaining respect for it abroad was a slow process, but it was successfully achieved through some intense periods of pressure. |

| Modern opinion, while sympathetic to and admiring of those involved in the struggle for independence, is much more critical of the efforts in the founding generation to build up the State and run a viable economy. Yet they did it in adverse circumstances without the possibility of recourse to outside aid. Travelling across England under escort by train on transfer from Dartmoor to Lewes Jail, Thomas Ashe, writing to his sister, wondered ‘will we ever see any tall chimney stacks in Ireland except those of the distilleries and breweries’. It was necessary to create a small and protected manufacturing industry for the domestic market. But the Sinn Féin economic model could only take the country so far. It did not have the answer to falling population and continuing emigration or the difficulty post-Second World War of meeting rising expectations. Too much social responsibility was outsourced to the Church. |

| We know the sequel, the progress and the stumbles, after a new strategy that involved an about-turn was adopted. We had to cope with and find some solution to the Northern Ireland conflict that did not involve the domination of one community over the other. Our commitment to the European Union transformed our relative position. National sovereignty today has less the absolute and indefeasible character claimed for it in the Proclamation, and is more about, in Emmet’s words, taking our place amongst the nations of the world. Unexpectedly, as a result of Brexit, we find ourselves likely to be further separated from our British neighbours. Probably while the process of negotiation and the politics will be bumpy, at the end of it all there will be a new modus vivendi which will be reasonably satisfactory, as Britain enters a form of external association with the EU. Ireland can hold its own in the EU, being well able to network, and there will be opportunities. |

| The La Touche family in the late 18th and early 19th centuries played a significant part in the economic, social and urban development of this country as well as creating an important financial institution, the Bank of Ireland, that survives to this day. Their contemporaries attributed to them an honesty and integrity that allowed them to make an important contribution to the Ireland of their time. Ireland today needs plenty of people willing and able to serve the public today in the same spirit. |